Bouncing Back

$1.6 million NIH grant awarded to team from Engineering, School of Medicine to study loss of motion after injury

Recovery after a traumatic or overuse injury isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach. Even after fractures have healed, soft tissue injuries often take far longer to resolve and, for some patients, full range of motion might never fully return.

A team of researchers at Washington University in St. Louis seeks to better understand joint contracture — or loss of motion — after an injury. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) recently awarded them a five-year, $1.6 million grant to continue their research and develop a combined treatment option using drug treatment and physical therapy to better restore range of motion following injury.

“We’re focusing on the elbow because this is a particularly challenging joint to heal,” said Spencer Lake, assistant professor of mechanical engineering & materials science in the School of Engineering & Applied Science. “These injuries are difficult to predict and treat.”

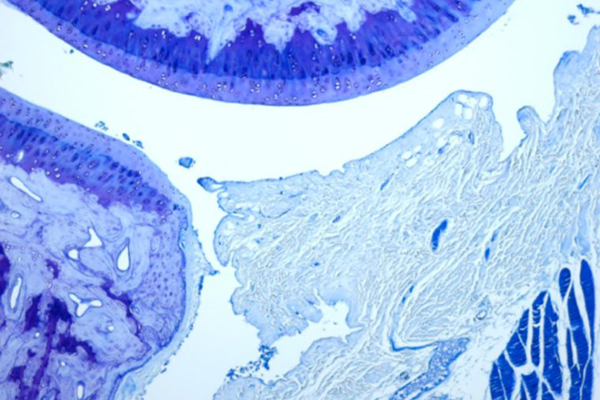

Lake and his collaborators at the School of Medicine — Aaron Chamberlain, MD, assistant professor of orthopedic surgery, and Ken Schechtman, associate professor of biostatistics — are using an animal model to study elbow joint contracture and identify which soft tissues contribute to range of motion loss. The research team will build upon previous work by evaluating how medications and physical therapy can improve recovery.

“Each of these injuries is different, and each patient responds differently,” Lake said.

“The elbow is especially unpredictable. You could have two patients with seemingly similar injuries: One may regain full range of motion while one might end up with a very contracted joint. We are hoping to identify key principles regarding prevention of joint contracture from our animal model that can be applied and transferred to patients for better treatment.”

Lake and his collaborators will focus on two drugs during their continuing research: one called losartan, typically is used to treat high blood pressure, and the other, simvastatin, is prescribed to treat high cholesterol. Both medications are FDA-approved and have shown off-target effects in other soft tissues, including unexpected benefits to tissue healing.

“The clinical application of these drugs has nothing to do with contracture,” Lake said. “Other studies have shown they have unintended, anti-fibrotic effects following injury. In preliminary studies in our lab, we observed a positive effect using these drugs in our model, so we’ll explore them in much more detail.”

This project also will investigate active exercise as a form of physical therapy, as well as whether either of the drugs plus physical therapy can provide synergistic beneficial effects. Once the treatment protocol is further refined, Lake hopes it could be used for other joints of the body that are also prone to injury.

“We are confident that the things we learn about how the elbow joint responds to treatment will be applicable to other joints, including contracture of the shoulder and knee,” Lake said.