In the media: Toxic legacy: WashU researchers look for ways to keep lead out of drinking water

Could adding a non-toxic compound to drinking water could prevent lead release?

>> Read the full article on St. Louis Public Radio

Dan Giammar collects something most people want to get rid of: lead pipes.

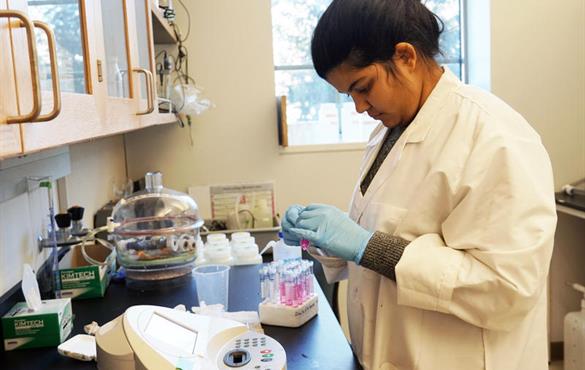

“This is just a great piece of lead pipe,” said Giammar, turning the smooth cylinder in his hands.The Washington University professor of environmental engineering is testing ways to keep lead pipes from dissolving and leaching into drinking water. Using old pipes from across the country, Giammar’s lab is working to understand whether adding a non-toxic compound to drinking water could prevent lead release.

Water pipes were often made of lead until the 1940s, partly because it’s a soft material that’s easy to bend.

Lead pipes also last an average of 35 years — more than twice as long as iron.

But they also make us sick.

We now know lead pipes dissolve over time and contaminate drinking water, causing a multitude of health problems from reduced kidney function to premature birth.

Despite early warnings from medical professionals in the 1920s, lead pipes were installed in cities across the country until World War II.

For its part, the lead industry led a robust campaign to promote the use of lead in household goods, including a 1923 advertisement in National Geographic announcing “Lead helps to guard your health.”

St. Louis, like many cities, installed tens of thousands of lead service lines, which connect the water main to individual homes. Today, there are an estimated 50,000 lead service lines remaining in the city, but Giammar said this isn’t necessarily cause for alarm.

To keep lead from leaching into the water, the St. Louis Water Department adjusts the water pH.

“Our concentrations of lead in the water are among the lowest in the country,” he said. “The relatively high pH of our water and the hardness of the water — which is the calcium and magnesium, and the alkalinity — seem to be quite protective against lead release.”