For engineers, a third option

Graduates don't have to work at a big company or get a professor job, they can start their own business

Jeffrey Czajka likely didn’t think that, as a systems biology and fermentation researcher at Washington University in St. Louis, he would be quizzing customers in the grocery store about their pet food preferences.

But, in 2017, a local startup approached his adviser looking to collaborate. That June, Czajka began working with Arch Innotek, a biotech company working out of BioGenerator Labs in the Cortex Innovation Community.At Arch Innotek, Czajka works with Yechun Wang, chief scientific officer, on bioengineered microorganisms that create phytochemicals for use in foods and other products.

“When the project first started, I thought I’d be doing strain analysis and fermentation optimizations,” said Czajka, a PhD candidate in the School of Engineering & Applied Science.

It’s foundational work that has to be done in any lab of the sort, and not a drastic departure from his work as a PhD student in the lab of Yinjie Tang, where Czajka works in metabolic analysis of different microbial cultures. Soon, however, his work with Wang and Arch Innotek started to take him places many researchers don’t go.

“Under Arch Innotek’s support, I had the opportunity to attend a conference where there were companies specifically in our field. We got to engage in interesting conversations with the companies, tech experts and business developers,” he said, to learn how the business side of biotech works.

For example, Czajka watched the CEO of Arch Innotek approach various tech companies. “ ‘We’re Arch Innotek,’ he’d say. ‘We use this kind of technology to make X, Y and Z, and this is what we can do right now. Is this something that would be of interest to you down the line?’”

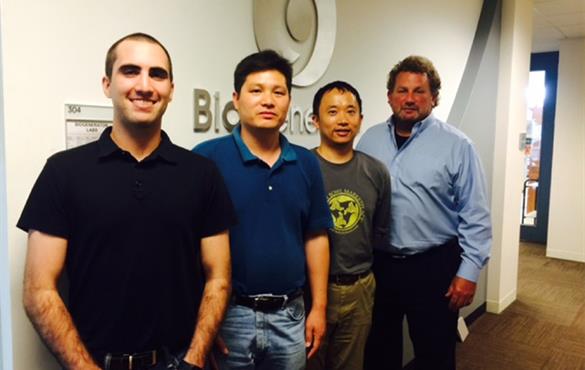

Learning about the business side of biotech is, in fact, a fundamental goal of the programs that brought Czajka and Arch Innotek together. Together, Arch Innotek and WashU were awarded three grants: a Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) grant from the National Institutes of Health; an STTR grant from the National Science Foundation; and an NSF INTERN grant (see Czajka, Tang and Wang at 2:15).

The STTR grants are designed to support research at startup businesses, while the INTERN grant is solely dedicated to providing support for non-academic research internships. Tang was the co-principal investigator on all three grants, which partially support Czajka’s stipend.

“Why is this company willing to invest in Jeff?” Tang asked. Czajka’s research in Tang’s lab has used “metabolic flux analysis,” a tool to understand and characterize metabolic pathways — a series of reactions responsible for processes such as creating energy or building proteins. “This tool is very variable and can provide a lot of knowledge for the company,” Tang said.

For Czajka, the opportunity to branch out beyond the lab is a bonus that led to some very un-lab-like situations. Which is how he ended up with a clipboard in the aisles of the grocery store. It was during the market discovery section of a four-week workshop for another NSF grant, Missouri I-corps program.

For the project, the workshop participants were designing an antioxidant for use in pet foods as an “all-natural” ingredient. They had to find out what customers wanted and what prices they can pay, so they headed to the store to ask such questions as “What kind of things are important to you when you’re buying pet food?” and “Do you look at labels? If there’s another product that’s similar, what would make you choose one product over the other?”

It was the opposite of working, head-down, in a lab. “It was nerve-wracking,” Czajka said, but a valuable, and in retrospect, a fun experience.

Czajka still has a few years left before he finishes his doctoral work. Last year, he also was the mentor for the WUSTL iGEM team and enjoyed teaching undergraduates in biotechnology research. He has yet to decide if he’ll go into academia or industry. But for Tang, the point of this collaboration was to show his students they have options.

“It used to be there were two routes after the PhD: work at a big company or get a professor job,” Tang said. “Now, they have a third route: They can start their own business.”

Noting that St. Louis had just been recognized as one of the top cities for life science startups, Tang said the opportunity for students to work with small companies is good for them and for the local economy. And, Wang has committed to working with students moving forward.

Even if after finishing his degree Czajka decides to trade in his clipboard for a lab coat, he has learned more than a few lessons that he’ll take with him. Perhaps surprisingly, one of the skills he found most valuable is communication.

“As scientists, our mission or our responsibility is to communicate science to the general public,” he said. “When you’re talking to a business or a marketing person, you have to know how to communicate what it is that you’re trying to achieve.”