Global pollution estimates reveal surprises, opportunity

Researchers’ hybrid dataset includes satellite images, modeling and air samples

It is not unusual to come across headlines about pollution or global warming and find that they reach different conclusions depending upon the data source.

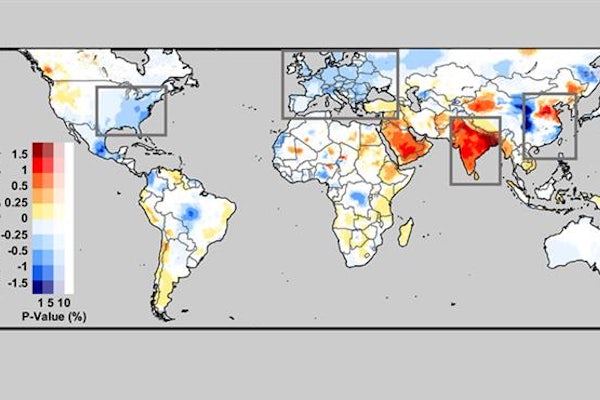

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis used a harmonized approach, incorporating data from multiple satellites and ground monitors with computer modeling to compile a comprehensive, consistent map of pollution across the globe. Their data spans 1998-2018, providing a current picture of the state of the world’s air quality that reveals some surprises, both for better and for worse.

The research was led by Melanie Hammer, a postdoctoral research fellow in the lab of Randall Martin, professor of energy, environmental and chemical engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering.

Results of their study that looked at PM2.5 — tiny particles that are able to make their way deep into a person’s respiratory system — were published June 3 in Environmental Science & Technology.

“Prior studies that look at long-term PM2.5 haven’t used data as recent as we have,” Hammer said. Older data can’t capture the results of many programs aimed at curbing pollution — even if they have been in effect for nearly a decade.

That turned out to be the case in China, where a significant drop in pollution in the recent past was the result of strategies begun in earnest around 2011. Other data sets don’t capture the drop.

And in India — another area of concern — the story was not as positive. “It seems there’s a bit of a plateau of PM2.5 levels,” Hammer said. Though still, levels are not rising as steeply as other reports may suggest.

PM2.5 refers to the size of particles — 2.5 microns. These tiny particles are created in nature, but also by human activities, including some manufacturing processes, car exhaust and the use of wood-burning cookstoves.

It’s not easy to measure the amount of PM2.5 on the ground because there isn’t any kind of comprehensive monitoring network covering the globe. North America and Europe have extensive monitoring systems, as does China. But, Martin said, “There are large gaps in ground-based monitoring. People can be living hundreds of kilometers away from monitors.”

To develop a comprehensive pollution map, then, ground-based monitors are simply insufficient.

To capture a global snapshot, Martin’s team started with satellite images of columns of atmosphere that spanned the ground to the edge of space. Using the established GEOS-Chem model, which simulates atmospheric composition, they could infer how much PM2.5 should be on the ground, at the bottom of any given column.

When comparing the predictions to actual levels measured by ground monitors, the agreement was striking. In fact, Martin said, “It’s the best level of agreement found to date.”

But the researchers still went a step further.

The agreement was great, but not perfect. So Hammer added the differences between the observed and predicted amounts of PM2.5 and expanded the ground-based predictions across the globe, filling in the massive gaps between monitors.

This extra step brought the observed and predicted levels of PM2.5 from 81% to 90% agreement.

Once they were able to take a good look at the most recent pollution levels around the world, the researchers saw some stark changes from previous trends. Particularly in China.

“We’re used to seeing just large, increasing trends in pollution,” Hammer said. But in China, “What we found, from 2011 to 2018, is that there actually is a particularly large negative trend.”

Elsewhere in Asia, the picture wasn’t as positive.

While pollution levels did not seem to be increasing in India, the country seems to be in a plateau phase. “The broad plateau of very high concentrations, to which a large population is exposed, is quite concerning,” Martin said. “It affects the health of a billion people.”

However, the takeaway from this research can be, on the balance, a hopeful one: It seems to show one possible way forward.

“The data Melanie’s analysis reveals is a real success story for air quality controls,” Martin said. “It shows they can be remarkably effective at reducing PM2.5.” Although scientists have known these controls contain the potential to make an impact, he said, “The changes in China are very dramatic, larger than we have seen anywhere in the world over the observational record.

“It illustrates a real opportunity to improve air quality through effective controls.”

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago, and the Health Effects Institute. It was partially supported by the Killam Trusts. GEOS-Chem input files were obtained from the GEOS-Chem Data Portal enabled by Compute Canada.