Saving front-line workers

In the early days of the pandemic, personal protective equipment was in short supply in the U.S., and its availability continues to be a problem globally, leaving health-care workers and their communities exposed. Jennifer DeLaney, MD ’97, has been on a remarkable journey leading a local effort to help

When SARS-CoV-2 started migrating across the globe devastating communities, Jennifer DeLaney, MD ’97, like so many others, watched the news with dismay. When health-care workers in Asia began getting infected and dying while caring for COVID-19 patients, she was horrified. Then the pandemic hit stateside, and the rush was on to secure scarce protective personal equipment (PPE) for those on the front lines.

DeLaney, a primary care physician in St. Louis, instructor in clinical medicine at the Washington University School of Medicine and at the time president-elect of the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Medical Staff Association, knew the importance of keeping health-care workers healthy. She also knew of the shortages of PPE in hospitals.

What began as volunteering to research how to make 3D printed face shields led DeLaney to an idea of making powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs). And what began as a desire to make 10 PAPRs for local hospital emergency personnel has led DeLaney to deliver hundreds of units to local, national and international health-care facilities in need. Her journey to this point, like much of life during the pandemic, has been surreal, yet it’s also been one filled with caring, collaboration and community.

The idea

Very early in 2020, in response to a shortage of PPE in hospitals, including face shields, N95 masks and respirators, Washington University and BJC HealthCare created the COVID-19 WashU/BJC Maker Task Force to provide solutions for medical supply challenges caused by the pandemic. The task force included technical experts and leaders from across the university, BJC and the broader St. Louis “maker” community. Wanting to lend a hand, DeLaney joined the Maker Task Force and reached out to local high school teachers in robotics, science and engineering to see if they could use their school’s 3D-printing capabilities to make face shields.

“While on a Facebook site for providers on how health-care workers were protecting themselves against COVID-19, I saw face shields and N95 masks were one way,” DeLaney says. “And while researching how to 3D print face shields, I also saw several references to something called a powered air-purifying respirator and a YouTube video on how to make one. I said, ‘Oh, maybe I should make that instead.’ To make one, though, you needed a medical device called continuous positive airway pressure machine, a CPAP.”

“I was looking for the motors to see if I could pilot a device. I was hoping to make maybe five or 10.” - Jennifer DeLaney, MD ’97

DeLaney and her medical partner, David Katzman, MD, an instructor in clinical medicine and former chief resident of the Department of Medicine at Washington University’s School of Medicine, immediately sent an email to their patients asking for any unused CPAP machines and snorkel masks. “I was looking for the motors to see if I could pilot a device,” DeLaney says. “I was hoping to make maybe five or 10, depending on how many motors we got and whether or not it was a feasible project, not having an engineering or technology background.”

The response was overwhelming. And one pivotal email DeLaney received was from a patient who works for Hunter Engineering Company, a St. Louis–based manufacturer of automotive service equipment. The patient offered to connect DeLaney with another WashU alum, Nick Colarelli, MSEE ’86, executive vice president for Hunter Engineering, who was also trying to help efforts to secure PPE.

“When it became clear that COVID was coming our way, we started talking internally here at Hunter, and the president, Beau Brauer, and chairman, Stephen Brauer [vice chair of Washington University’s board of trustees], asked me to look into what we could do to help,” Colarelli says. “One of the first things I did was call WashU Professor Philip Bayly [the Lee Hunter Distinguished Professor in mechanical engineering and materials science]. I knew that he and Dean [Aaron] Bobick were on the Maker Task Force, and I told him that we’ve got all this labor available and all this engineering and manufacturing expertise available, and then asked what we could do to help. His answer was face shields; that’s what people needed. So, we started on that, and we scoured the earth for an appropriate plastic for face shields. This was in early March 2020. And we just had no success in coming up with the material. We were calling everyone we knew and talking to other companies, our suppliers, and we basically struck out.”

So, when Colarelli learned of DeLaney and her idea of a new powered air-purifying respirator, he was ready to assist in the effort.

The high school robotics and engineering teachers who DeLaney had been working with made the first prototype of the PAPR. Then Hunter Engineering took it from there.

“Together with three of my engineers — one mechanical, one electrical and one manufacturing — we met with Dr. DeLaney,” Colarelli says. “There in her office on the counter were a bunch of parts all loosely wired up. She demonstrated the concept, which was basically to take a blower motor out of a CPAP, hook electronics to it and run it through a filter. And her first prototype used a scuba mask. She asked if we could help, and I said yes. Then she said, ‘I need it fast. I need to take one to MoBap tomorrow,’” Colarelli says with a chuckle.

“We brought the parts back to Hunter, packaged them in a plastic box, attached the box to a belt, hooked a battery to the belt as well, and got all the fittings for the hoses to hook up,” Colarelli says. DeLaney picked up the device from Hunter Engineering and then came back the next day with pictures of an ER nurse wearing it, and said they loved it. “Then she asked: ‘When can I have 10 more?’”

When Hunter Engineering put out a call for CPAP machines, they received more than 500. Knowing that respirators were in short supply and some local hospitals didn’t have any at all, DeLaney and her team were thinking how their new device could possibly help out in the ICUs at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and beyond. Per regulations, though, the PAPR couldn’t be considered for widespread use unless it was approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health (NIOSH).

Talking with a few university board members on how to garner such government approval, DeLaney and her team found advice and then some: additional financial support to continue to expand their work.

On the commercial market, a similar medical device runs between $1,800 and $2,200. Up to that time, DeLaney had donated her own money to get the effort started, in hopes of making 10 devices, and others had donated their time and efforts, including a massive number of hours by Hunter Engineering.

With a new goal of NIOSH emergency use authorization, the team fine-tuned the device and put together a several hundred-page application for submission. Hunter Engineering enlisted personnel throughout its company to help in this daunting task.

Then in April 2020, NIOSH changed its requirements and no longer would accept tight-fitting face coverings. That meant DeLaney and her group could no longer use the scuba masks they’d been using on the PAPR. They would now need a loose-fitting hood.

“They changed the requirements. First, we had to go with a loose-fitting hood. We also had … to scramble and design a flow sensor. We did that over a weekend, and it was really fun.” - Nick Colarelli, MSEE ’86

“I know they were dealing with an evolving situation just as we were,” DeLaney says, “but it made our project more challenging because what we were aiming for was constantly changing.”

At each bump in the road, DeLaney continued to focus on the goal of protecting front-line health-care workers, and the community rallied behind the team’s efforts. NIOSH referred DeLaney to a biomedical engineer at the Veterans Health Administration Innovation Ecosystem in Seattle who had previously designed a hood. And Hunter Engineering continued to dedicate four engineers full time toward the continued development of the device (and 41 others were clamoring to help).

“They changed the requirements,” Colarelli says. “First, we had to go with a loose-fitting hood. We also had to monitor the flow of the air, so we had to scramble and design a flow sensor. We did that over a weekend, and it was really fun.” The engineers also 3D printed several parts and made other improvements on the design.

“The biggest challenge for me,” DeLaney says, “is that in medicine, when you make a decision and you write an order, it happens. The same is not true with government regulation and engineering. I think engineers have a greater tolerance for the fact that it takes a couple of iterations to get things perfect.

Achieving approval

While many cities across the U.S. were still on stay-at-home orders in early May 2020, DeLaney drove the 600 miles from St. Louis to Pittsburgh to present the prototype of the new powered air-purifying respirator for government approval.

In June, DeLaney and her team learned they’d need a new filter. Per new NIOSH requirements, the team had to use a filter made for workers in hazardous places like mines, although in a clinical setting they needed to filter out bacteria and viruses. Yet again, the community stepped up, including a company in Creve Coeur, Missouri, which provided the new filter, and WashU’s Aerosol Impacts and Research Lab, which tested it.

A second submission in August led to a request for additional safety features, such as a kill switch to turn off the motor if the filter was removed inadvertently.

DeLaney submitted a third application in October, and the device was certified in November. By then, DeLaney and Katzman had formed a charitable organization, PAPR Force, and their prototype was one of only six PAPRs approved worldwide for use during the public health emergency.

After a few hiccups, like a COVID outbreak at the manufacturing facility, the first batch of devices was delivered to Washington University the first week of January 2021 and distributed to ICUs at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Missouri Baptist Medical Center. Then in February, Hunter Engineering donated 50 units to hospitals in Jackson, Mississippi, home to one of Hunter’s factories, one that has been helping manufacture the devices. Although PAPR Force had produced an instructional training video, DeLaney traveled to Jackson to train four ICU and emergency department staffs in one day. This was their first big shipment, and she wanted to make sure the units fit comfortably and the health-care workers understood how to use them safely.

“The people were so grateful, and it was so heartwarming. It’s been such a wonderful opportunity for me to give back,” DeLaney says. “What I do on a daily basis in medicine is highly personal, and it’s valuable for the person I’m working with. But I’ve never had the opportunity before this to do something system-wide and to protect a larger group or groups of people. The idea of protecting the community or the community’s hospital staff is very exciting.”

A global need

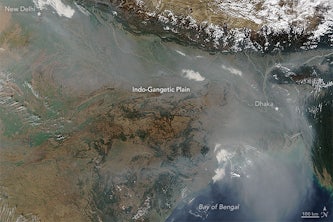

As the need for PPE declines in the States, it continues to grow across the globe. Rates of infection are soaring in places like India. In Peru, they’ve lost 400 physicians to COVID-19 since the pandemic began. It’s imperative, especially in countries with very few health-care workers, to keep those on the front lines safe.

“If the staff isn’t there, and nobody knows how to run the ventilator, you essentially don’t have a ventilator,” DeLaney says. “And I think there are some 10 countries in Africa, for example, that don’t have an ICU bed, not one. Most of these countries don’t have the capacity to treat highly ill people.”

Against this dire backdrop, PAPR Force’s efforts are ramping up.

“I’ve been approached by other donors who would like to help protect health-care workers from COVID-19,” DeLaney says. “Simply put, we will donate as many units to low- and middle-income countries as our contributions allow.”

Washington University’s School of Medicine is donating 300 units, including shipments to international collaborators (hospital centers and medical schools) in Kolkata and Mumbia, India, and Lima, Peru. DeLaney collaborated with Vicky Fraser, MD, the Adolphus Busch Professor of Medicine and chair of the Department of Medicine, and Stephen Liang, MD, associate professor of medicine in both the infectious diseases and emergency medicine divisions, who conducted a study on the PAPR and contamination. They’ve been coordinating international shipments from the WashU side. Additional units are on their way to Guatemala, and queries have come in from Bosnia, Cameroon, Sri Lanka, Honduras and Paraguay. Hunter Engineering donated 20 to Bangalore, India, as well.

“I’m trying to ramp up manufacturing as well as work on the logistics of all these international shipments,” DeLaney says, who is having to get approval from the various hospital systems and potentially each country’s health ministry, as well as deal with any customs and tariffs issues.

“In most of these low- and middle-income countries, the number of physicians per population is very low, like 100-fold or 1,000-fold less than in the U.S. And in some places, if you have an ICU and you lose your one attending, you could not replace that person. There’s literally no one else there to run the ICU,” DeLaney says. “To give these to communities who don’t have protection, who don’t have adequate vaccination, who don’t have the resources to handle the highly complex care, that is the highest use of this device to me.”

“Dr. Delaney has been extraordinarily committed to creating a new PAPR to help protect health-care workers from COVID,” Fraser says. “Designing the device and getting it NIOSH approved took a Herculean effort. This new PAPR will be particularly helpful in resource-limited settings across the world, and we’re working closely with our global health programs to help distribute them across several continents. We’re incredibly grateful to Dr. Delaney, the donors and the Hunter Engineering team for their efforts to protect health-care workers.”