Engineering a safer future against infectious disease

Quick detection of the COVID-19 virus — in the air and in one’s breath — offers hope in the nearly four-year struggle against the disease and its variants. A collaboration of WashU scientists is leading the way

We’ve come a long way in the 43 months since March 2020, when the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic in the wake of the SARS-CoV-2 virus outbreak, but still we can’t shake it. Long COVID remains a mystery and a new variant has popped up. A renewed booster shot is now available, and nearly four years later, masking remains an important part of the public health conversation.

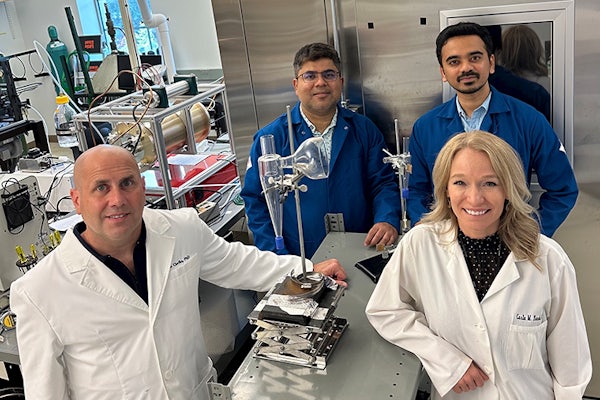

But there is reason for optimism, thanks to a multidisciplinary team of Washington University in St. Louis researchers. This summer, researchers from the School of Medicine and the McKelvey School of Engineering published two papers announcing the development of two new devices that ultimately could go a long way in dealing with this virus — and ultimately viruses that could cause future pandemics.

The first was an air quality monitor that can detect SARS-CoV-2 in public spaces, the second a breathalyzer that can provide a quicker diagnosis of individuals. And both happened because of a collaboration between WashU scientists who had never met in person and wouldn’t do so — because of social distancing — for more than a year.

“One of the silver linings of the pandemic,” says Rajan Chakrabarty, the Harold D. Jolley Career Development Associate Professor of energy, environmental & chemical engineering in McKelvey Engineering, “is that it forced collaborations between disciplines that otherwise would not have taken place.”

Read the full story here.