Clearing the Air

Jay Turner works to identify risks and solutions to poor air quality

As a high school student sailing under clear skies on the San Francisco Bay, Jay Turner would gaze toward shore, gauging weather conditions by watching the banks of fog high on the city’s hillside.

Later, as a University of California, Los Angeles freshman in 1980, he noted the similarity as he stood on the docks in Marina del Rey and spied the smog east over Los Angeles. But as he sailed into the Pacific Ocean and peered back at shore, he realized the smog also blanketed the marina he’d just left.

The smog wasn’t just inland. It was everywhere.

“You realize you’re in it, too, and that visual perception of your local environment did not completely align with reality,” recalled Turner, associate professor of energy, environmental and chemical engineering. “That was a moment that moved me.”

That experience, along with a research opportunity at UCLA in his sophomore year, propelled Turner into a lifelong career studying air quality in locations as close as St. Louis and as far-flung as Hong Kong.

It’s also led to a 23-year teaching career at Washington University in St. Louis, where Turner was recently appointed vice dean for education in the School of Engineering & Applied Science — a new role in which he will lead the schoolwide effort to enhance the undergraduate student experience in what we teach and the best way to teach the next generation of engineers and leaders, said Aaron Bobick, dean of the Engineering school, when announcing Turner’s appointment to the new post.

The appointment, which began Sept. 1, heaps new responsibility onto Turner’s already-full plate. In addition to managing a full slate of research projects, Turner serves on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Science Advisory Board and chairs that board’s Science and Technological Achievement Awards committee and Risk and Technology Review Methods panel.

All of this while teaching classes, leading to a 2016 Emerson Excellence in Teaching Award and five “Professor of the Year” awards from the school’s graduating class.

Turner said the new role is exciting and will focus on both pedagogy and effective teaching strategies. While still in the formative stages, the goal is clear: Apply the same rigor and innovation to the education side of the school’s mission as it does to the research side. How can professors introduce more “active learning” in the classroom? How can they challenge students with a more project- and problem-based focus on their education?

“There are innovations in teaching, and there is no reason to assume the tried-and-true approaches of the past are the most effective,” Turner said. “One of my roles is to help enable faculty to embrace evidence-based teaching practices. This requires a suite of supports and structures.”

Curriculum reform is also in the making. For example, Engineering is in discussion with programs across campus to develop joint majors, such as a joint degree with the Olin Business School and a joint degree with mathematics and computer science.

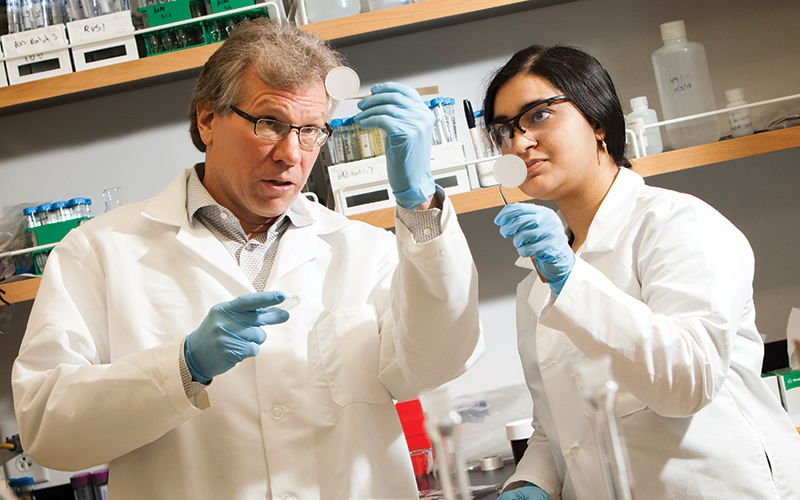

While Turner begins his work to shape the trajectory of undergraduate education within the engineering and applied sciences, he is also managing the changing trajectory of his own research. Over two decades of work in environmental science and air quality, Turner said his research has increasingly moved toward studying the health effects of pollution.

“While I’m not a health scientist, I collaborate extensively with health scientists, and the interactions are very rewarding,” Turner said.

One paper published recently with environmental health researchers from Emory University in Atlanta studied how certain airborne pollutants affected visits to emergency rooms in the St. Louis metropolitan area. The study found strong correlations between specific health risks and certain types of pollutants. High levels of airborne carbon particulates, for example, drove more ER visits for congestive heart failure. Patients complained to emergency room doctors more of asthma and wheezing when ozone and nitrogen dioxide levels spiked.

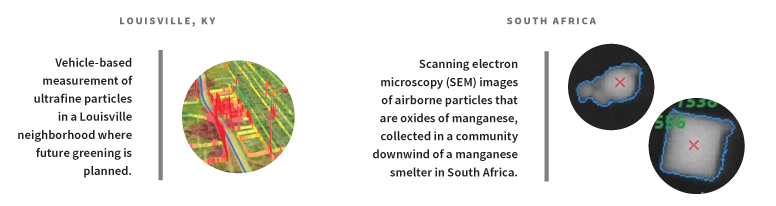

Turner also is collaborating on a study led by Brad Racette, MD, the Robert Allan Finke Professor and executive vice chairman of neurology at the School of Medicine, to determine whether airborne manganese is a risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease.

“What’s really impressed me is how we, the broad research community, have been able to identify risks that are caused by air pollution.”

— Jay Turner

“Smaller and smaller risks have been detected because we have sharpened the tools used for conducting measurements, estimating exposures and probing relationships with health outcomes.”

For Turner, it’s not just about identifying risks, but solutions. He recently collaborated on a half-million-dollar study of lead emissions at four general aviation airports where small, piston-engine aircraft still use lead-based fuel. Airport operators sought information to understand how those emissions affect lead levels at and near airports and how that information can guide future abatement strategies.

In October, the City of Louisville, Ky., launched a collaboration with nonprofit organizations, a local private school and researchers — including Turner — to measure whether a buffer of trees and shrubs between the school and a neighboring highway can improve air quality on campus. Turner created and oversees the air-monitoring plan for the school.

After a career of collaborating with other researchers around campus, the nation and the globe, he’s particularly excited to collaborate with colleagues at the School of Engineering & Applied Science, driving curriculum innovations, best practices in teaching and improving undergraduate education.

“WashU is a distinctive place to work,” Turner said. “You can see why prospective students fall in love with the campus when they visit. The sense of community, the collaborative nature — it’s really impressive and it’s something I don’t take for granted.”