Reimagining synthetics

Learn how Fuzhong Zhang uses synthetic biology to create new products that could one day replace fossil-derived materials and fuels

In his wallet, Fuzhong Zhang carries a small slip of paper from a fortune cookie that says, "Avoid unchallenging occupations — they will waste your great talents."

Though he set out to be a chemist — in itself a challenge — earning three degrees in chemistry, ultimately, he became a chemical engineer who has won nearly every young investigator award available to engineers. During his doctoral work at the University of Toronto, he discovered the work of Jay Keasling, professor of chemical engineering and bioengineering at the University of California, Berkeley, and a pioneer in the growing field of synthetic biology. Zhang decided on a career in engineering. As a postdoctoral researcher in Keasling's lab, he learned how to use engineering tools to skillfully alter the chemistry of cells.

Zhang, associate professor of energy, environmental & chemical engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering, now runs a busy lab with 10 doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers using synthetic biology to create new products, such as stronger spider silk and better biofuels that could one day replace fossil-derived materials and transportation fuels. He holds three U.S. patents and is applying for two more.

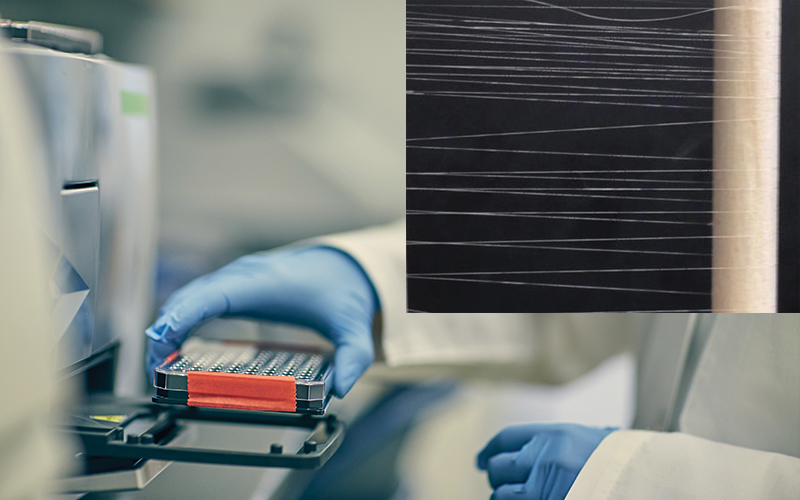

One of his projects uses engineering tools to reprogram the biosynthetic machinery and metabolism of microbes to produce high-performance protein materials, leading to a variety of new applications. His team has engineered bacteria to yield synthetic spider silk that is as strong and tough as natural spider silk fibers, the toughest material in nature. They are currently expanding the biosynthetic power of microbes to create novel proteins that can be even stronger and tougher than spider silk and more suitable for scalable production. His vision is to one day produce various fiber products that could be used to stitch wounds or woven into fabric to stop bullets. His team also engineered bacteria to produce sticky proteins that mimic the underwater adhesive proteins found in mussels and use them for sealing wounds and repairing cracks in underwater vessels.

"With better understanding and more experience with engineering cells, we can create novel materials that nature does not evolve but may have more attractive properties and be able to perform functions that natural materials cannot do," Zhang said.

Zhang's early career awards

- Society for Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology (SIMB)

- Biotechnology and Bioengineering Daniel I.C. Wang Award

- ORAU Ralph E. Powe Junior Faculty Enhancement Award

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)

- Office of Naval Research

- Air Force Office of Scientific Research

- National Science Foundation

- Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) of the U.S. Department of Defense

- Human Frontier Science Program Organization

Education & Training

- Postdoctoral research: University of California, Berkeley

- PhD, University of Toronto

- MS, McMaster University

- BS, Peking University

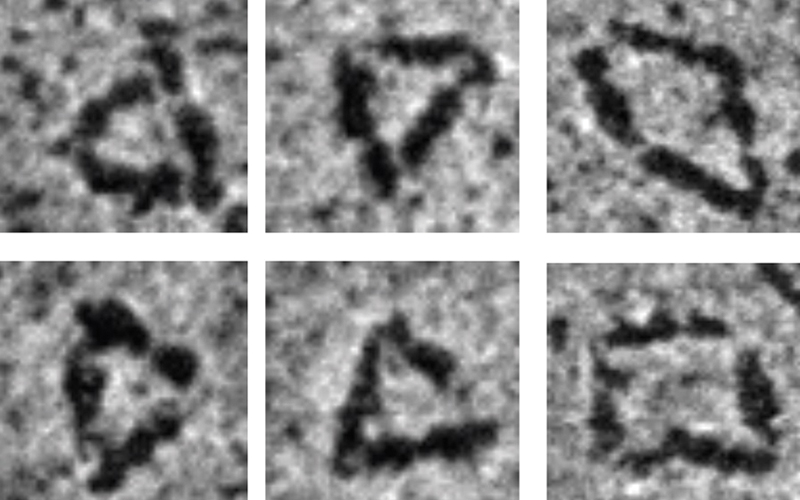

Zhang also is working to develop tools that other microbial engineers can use to make their work more reliable and efficient. He and his team discovered that genetically identical microbial cells have different work ethics. His team developed a quality-control tool that can keep the hard-working, high-performing cells working while eliminating the low-performing cells. Another tool from his lab allows cells to constantly monitor their environment and their own metabolism to adjust their biosynthetic performance according to those environmental changes.

These and other projects underway continue to motivate Zhang to solve problems.

“We can create novel materials that nature does not evolve but may have more attractive properties and be able to perform functions that natural materials cannot do.”

— Fuzhong Zhang

"The potential of synthetic biology and microbial engineering excites me," he said. "Very often, I feel the potential is beyond my imagination. When reading scientific news or articles that discuss current problems, I always think whether these problems can be solved by synthetic biology. We have the microbial engineering tools in our hands; with a quantitative understanding of the problem, we may have the opportunity to solve it by precisely controlling the metabolic behavior of engineered cells."

Zhang's expertise in synthetic biology has led to a variety of collaborations at Washington University. With Gautam Dantas, professor of pathology & immunology at the School of Medicine; Yinjie Tang, professor, and Marcus Foston and Tae Seok Moon, both associate professors, all in the Department of Energy, Environmental & Chemical Engineering, Zhang is collaborating on a project to model, design and engineer Rhodococcus Opacus mutants to produce advanced biofuels and bioproducts from lignin, an organic polymer in the cell walls of plants that is usually discarded. He also is working with Srikanth Singamaneni, professor of mechanical engineering & materials science; with Guy Genin, the Harold and Kathleen Faught Professor of Mechanical Engineering; with Rohit Pappu, the Edwin H. Murty Professor of Engineering; and with Jianjun Guan, professor of mechanical engineering & materials science on various new protein materials.

Photo by Devon Hill.

"We understand how cells work and can engineer them to make a lot of useful materials, but we need our collaborators to tell us what molecules have what properties so that we can synthesize the right products," he said.

His creativity and innovative drive are recognized throughout the field.

"Fuzhong Zhang is a really innovative researcher who effectively uses fundamental knowledge and applies it to solve challenging problems," said Pratim Biswas, the Lucy & Stanley Lopata Professor in the McKelvey School of Engineering, assistant vice chancellor of international programs and chair of the Department of Energy, Environmental & Chemical Engineering. "With his colleagues Yinjie Tang, Tae Seok Moon and Marcus Foston in the biocluster in the department, he works very effectively to advance the science and applications of synthetic biology and protein engineering. It is great to have a colleague who does not hesitate to operate out of his comfort zone and challenge his group to come up with innovative applications."

Although Zhang already is involved in many projects, the innovative applications keep coming, he says.

"Ideas often come quickly, but the real question is which one we should pursue and which one will result in bigger impacts," he said. "I always remind myself that a hot topic with readily available funding may not be worth pursuing if its future is unclear."

And he is definitely looking ahead.

"When I retire, I would like to see people using products or technologies developed from my lab," he said.

and aid in drug delivery.