Focused ultrasound technique gets quality assurance protocol

Hong Chen and team develop protocol to ensure safety, consistency

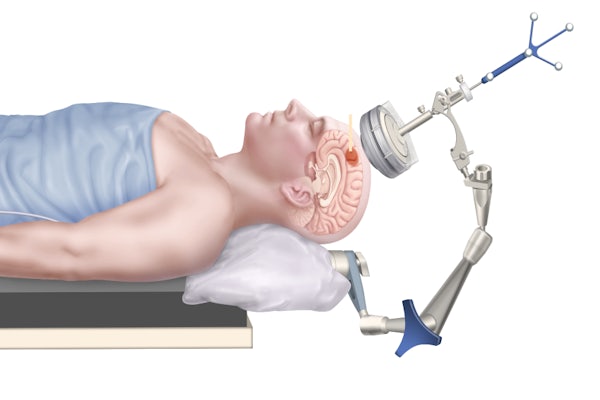

For the past several years, Washington University in St. Louis researchers have been using focused ultrasound combined with microbubbles to target an opening in the tough, protective blood-brain barrier to deliver drugs or retrieve biomarkers. However, the fast-developing technology has lacked a strategy to ensure that it functions safely and consistently.

To meet this need, Hong Chen, associate professor of biomedical engineering and of neurosurgery in the School of Medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, and her team, including first author and doctoral student Chih-Yen Chien, developed a quality assurance protocol to ensure their guided focused ultrasound device and treatment is safe and functions consistently. Results of the study to test their protocol are published online March 25, 2024, in eBioMedicine.

Focused ultrasound (FUS) uses ultrasonic energy to target tumors or tissue in the brain. Once located, the researchers inject microbubbles into the blood that travel to the targeted tissue then pop, causing small openings of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). These small openings allow two-way traffic for drugs to be delivered or biomarkers from a tumor or other brain diseases to pass through the BBB and release into the blood. After years of developing the noninvasive technique, Chen and collaborator Eric C. Leuthardt, MD, the Shi H. Huang Professor of Neurological Surgery, and a professor of biomedical engineering, of mechanical engineering and of neuroscience, are using the technique in human clinical trials.

The team developed a quality assurance strategy that incorporated an acoustic sensor into their FUS device. The sensor passively captures acoustic signals to evaluate three quality assurance functions: to ensure that the FUS device functioned consistently; that acoustic coupling, or a gel that allows the signals to transmit from the body to the transducer, could detect air bubbles trapped in the transducer; and to evaluate that the treatment procedure was consistent. Ultimately, they found that their passive acoustic detection protocol could be integrated with a clinical FUS system for quality assurance of the procedure.

“The protocol allows us to assess that the device is working properly before each procedure, evaluate the acoustic coupling quality, and monitor the process of the FUS-induced BBB opening,” Chen said. “Establishing these protocols is critical to advancing the FUS-induced BBB opening in clinical practice.”

The FUS device passed the quality assurance test in nine of the 10 patients in the study. When they tested the acoustic coupling, four of the nine cases failed on the first try. This test was designed to assess whether air bubbles were trapped in the FUS probe water bladder and the ultrasound gel. Such trapped bubbles could reflect the ultrasound wave and decrease the acoustic energy delivered to the brain. The test was performed repeatedly until it passed quality assurance in three-fourths of cases.

The FUS procedure itself passed quality assurance testing when the cavitation activity of the microbubbles —when the bubbles burst and emit sound waves —after injection showed a pattern of a fast increase followed by a return to baseline.

Chien said the proposed strategy was innovative and easy to implement.

“Without a systematic and quantifiable approach to evaluate FUS devices before each procedure, the functionality of the FUS system cannot be guaranteed,” she said. “Our study is the first to evaluate passive acoustic detection-based quality assurance for FUS systems with applications that can be extended beyond BBB opening to include other applications, such as ultrasound neuromodulation.”

Chien C-Y, Xu L, Yuan J, Fadera S, Stark AH, Athiraman U, Leuthardt EC, Chen H. Quality Assurance for Focused Ultrasound-induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening Procedure Using Passive Acoustic Detection. eBioMedicine, online March 25, 2024. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105066

Funding for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health (R01CA276174, R01MH116981, UG3MG126861, R01EB027223, R01NS1284610).